This post if for anyone who is interested in issues pertaining to technology and how it shapes culture. I wrote a post touching on this a few weeks back and there was a good one Gene Veith linked to as well (Man’s Prosthetic God: Technologies of Glory…)

I’m doing it tomorrow – taking a critical look at how information technologies, particularly “Big data”, are something to look at with a critical eye – especially as regards academic libraries. Overall though, it is quite far-reaching and gets quite deep quite fast, using robots and science fiction as a springboard. Here are the slides I am using with the text below:

Here is the abstract:

The desire to create automatons is a familiar theme in human history, and during the age of the Enlightenment mechanical automatons became not only an “emblem of the cosmos”, but a symbol of man’s confidence that he would unlock nature’s greatest mysteries and fully harness her power. And yet only a century later, automatons had begun to represent human repression and servitude, a theme later picked up by writers of science fiction. Man’s confidence undeterred, the endgame of the modern scientific and technological mindset, or MSTM, seems to be increasingly coming into view with the rise of “information technology” in general and “Big data” in particular. Along with those who wield them, these can be seen as functioning together as a “mechanical muse” of sorts – surprisingly alluring – and, like a physical automaton can serve as a symbol – a microcosm – of what the MSTM sees (at the very least in practice) as the cosmic machine, our “final frontier”. And yet, individuals who unreflectively participate in these things – giving themselves over to them and seeking the powers afforded by the technology apart from technology’s rightful purposes – in fact yield to the same pragmatism and reductionism those wielding them are captive to. Thus, they ultimately nullify themselves philosophically, politically, and economically – their value increasingly being only the data concerning their persons, and its perceived usefulness. Likewise libraries, the time-honored place of, and symbol for, the intellectual flowering of the individual, will, insofar as they spurn the classical liberal arts (with the idea that things are intrinsically good, and in the case of humans, special as well) in favor of the alluring embrace of MSTM-driven “information technology” and Big data – unwittingly contribute to their irrelevance and demise as they find themselves increasingly less needed, valued, wanted. Likewise for the liberal arts as a whole, and in fact history itself, if the acid of a “science” untethered from what is, in fact, good (intrinsically), continues to gain strength.

What follows is the text of my talk, which I have decided to read, both in order to keep it focused (I tend to wander…) and enjoyable to listen to…. It is the shorter and more direct executive summary of the much longer paper (book) that is available here: http://eprints.rclis.org/22750/

NOTE: link above has been updated to get you to the actual paper.

Why Big data is not “good enough” for the library’s soul – or yours

Librarians are like any other human being in that they like to feel that they have some control – some order! – over the chaos (OK, it is probably more so for us). And right now, many in the library world, seeking out a stable rock, seem to be falling over themselves to get more involved with things like MOOCs and Big data – perhaps the “evidence-based” and “data-driven” stallions we want to attach our carts to! I think this is rather akin to sleeping with the boss – or the person perceived to be the boss – in hopes of economic and political gain (i.e. that they to, might be “big” or at least “bigger” in the world). But when it comes to looking for whom to hook up with, there are solid persons – “men with chests”, as C.S. Lewis once put it – and there are the players who eventually leave you in the lurch.

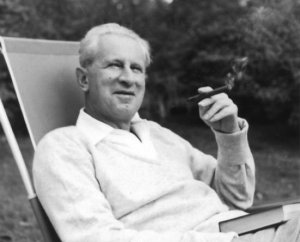

My mind has been on C.S. Lewis a lot lately, the literary giant and foremost Christian intellectual of the 20th century. Getting ready for this library technology presentation, I had composed a rough draft of 40 some pages – with 32 pages of additional footnotes (at end it is 89 total pages). My mind was brought back to Lewis and his ability to saliently communicate his point to most everyone in a few, well-chosen words – using good analogies and illustrations to make understanding big ideas possible.

Follow me here as I try to be like Clive. First of all, let’s notice that the idea of Big data grows out of the scientific method and that matters of science and technology are rich fodder for science fiction, a favorite genre of librarians. I think we would be wise to note that in science fiction, as the cultural historian of religions Robert M. Geraci says, we constantly see two intertwined themes: not human control and success but rather salvation and damnation by technology. In his memorable words: “fear of technological wrath accompanies the hope of a new Eden”. Along with this, he notes that we feel both “fear and fascination” in the presence of advanced robots. Why might this be?

The answer is bit complex, but I think is actually quite clear – and it is amazing how it connects up with notions of Big data. We can observe that the desire to create robots, or “automatons”, is a familiar theme in human history, and during the age of the Enlightenment mechanical automatons became not only an “emblem of the cosmos”, but a symbol of man’s confidence that he would unlock nature’s greatest mysteries and fully harness her power. And yet only a century later, automatons had begun to represent human repression and servitude, a theme later picked up – as noted above – by writers of science fiction. Western man’s ultimate confidence was undeterred however, and now it seems that the endgame of the modern scientific and technological mindset (or MSTM) is increasingly coming into view – the rise of “information technology” in general and “Big data” in particular signal this.

In the rest of this article I’ll explain a) why I think the endgame of the MSTM syncs with Big data and is becoming ever more clear ; b) how this mindset is distinct from science and technology per se ; and c) how libraries must recover and use good, classical philosophy to shun MSTM while using science and technology with wisdom and discernment.

Let’s start exploring MSTM by means of Big data and robots. In their recent book, Uncharted: Big data as a Lens on Human Culture, scientist-humanist hybrids Erez Aiden and Jean-Baptiste Michel begin by asking a provocative question: what if there was a robot that could be programmed to read all of the world’s books and then tell you what it had read? They then let you in on the surprise – there really is such a robot, and it is none other than Google’s n-gram viewer, which allows users to query – in the millions of books that Google has scanned – word and phrase frequency over a period of the last 200 years.

Leave aside for now the issue whether or not that robot, like IBM’s “Watson”, is really “understanding” or “telling” anything. Whatever the case, surely the technology that allows us to do things like this and more, is, as Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee note in their new book, The Second Machine Age, “a gift of God”. They continue this quote from Freeman Dyson, who also says that it is “perhaps the greatest of God’s gifts”. I am not so sure I can go as far as the second quotation does. Perhaps it has something to do with the little known fact that a substantial amount of the innovation that happens on the internet comes directly out of the pornography industry: evidently the desire for sex and money are two things that, to a large degree, inspire and drive technological development.

I am going to continue talking about porn here, and I promise that I am not doing that to keep your attention, but that I will have a larger point. Of course, this industry is giving people what they want, and the choices that they want – that is, the visual allure of particular human bodies (and perhaps, in the future, much, much more). Why does it all happen? It is simple really: the consumer of pornography consumes for the purposes of making himself (or, increasingly, herself) feel better – seeking the ever-fleeting promise of emotional and physical intimacy and, importantly, “feeling alive” – salvation. On the part of the porno-pushers, it means that they get to do what they love as well as consume the pocketbooks of the consumers – so long as they have a workable business model. It’s a win-win for everyone and when “done right”, no one gets hurt – or so it seems to those involved.

So what is the larger point? Well, does pornography have anything in common with computers – with “information technology” and the MSTM? It does. Consider the following: how do computers – which we can really just call robots – “know” us? I think it is easy to see how. Recently, in an interview with the director of the New York Public library tech-culture guru Jaron Lanier, when asked to share seven words that might define him, answered in a joking but semi-serious way, “our times demand rejection of seven word bios.” Doing that, Lanier explained, is a form of disempowerment because “you are creating database entries for yourself [i.e. “putting yourself in standardized forms”] that will put you into somebody’s mechanized categorization system.” As stated in Don DeLillo’s award-winning 1985 fictional novel “White Noise”: “…you are the sum total of your data. No man escapes that.”

Today, the world’s most powerful computers “harvest”, analyze, and build intricate computational models with your data – with all the other data – not only to spy, buy and/or sell, but to use as leverage to automate more and more work, push risk on to others, etc. As Jaron Lanier says, “Big data is people in disguise” – whoever we are talking about. But those in charge of sizing up your data will be tempted to increasingly determine your value according to it alone, just as the porn stars’ are really only measured by their pixels. In other words, never before has the phrase “nothing personal – just business” been truer.

If this doesn’t sound too concerning to you, consider in more detail just what is happening already, and will be so more and more: the robots who do this operate using the “useful fiction” – or, more accurately, the ones programming the robots do this – that through a combination of some information about yourself – culled from structured and unstructured data sources – and some workable mathematical models and algorithms, you can be known – insofar as necessary for the goals they think best (and how can you doubt that they care?). Yes of course, maybe the maker can’t really understand you on a deep level, but the maker, through the robot, can see evidence of what you do. And that is all he needs: taking account of this “works” for him regarding the things he wants to do: sell things to you, push risk on to you, prevent terrorism, perhaps even genuinely help you, etc.* It is all “good enough”.

Even if by this time, real trust in other human beings is in the process of leaving the building – even if it is something we are slow to detect, this continual encroachment of the MSTM’s fruit.

Anyone who knows something about the origin of computers should not find it surprising that some who use powerful computers are tempted to reduce what is complex into a false simplicity. Alan Turing invented the computer based on his own idea – his own model – of how the brain operated and how human beings communicated. After the computer begin to dominate our lives, it became more and more common to think about the brain – and our own communication as human beings – in terms of the computer itself and computer networks. As far as it pertains to academia, this happened in the sciences as well as the humanities. Jaron Lanier even talks about how words like “consciousness” and “sharing” have been “colonized” by Silicon Valley nerd culture. Can we say that as we increasingly give ourselves to technology without reflection and personally constructed levies, we see that it is not so much that the robots resemble us, but that we resemble the robots?

Are we, no longer intimidated by computers, simply just getting used to this – this soft mechanical touch? And really – who are our electronic devices (our “little robots”) – and all our online accounts – primarily there for?

I think that one can also see with increasing clarity how the MSTM affects us as we live out our economic lives. In her helpful Chronicle of Higher Ed. piece, Jane Robbins, speaking of the phenomena of “Massive Open Online Courses” or MOOCs, makes the following observation: “[MOOCs] retain their indifference to admission criteria (for now, although there is some movement toward elite MOOCs) and to retention, which means they don’t really care about whether students complete or not—but they do care about who completes, and why (or why not), and perhaps what can (or cannot) be successfully taught this way”. Here we see all of education – enhanced by the powers afforded it through technology – reduced to the crassest of business concerns in a rather extreme way. In the ancient world, there were certainly many traveling teachers who were happy to take your money. And yet, in their business model, they had to pay some attention to you – they had to treat you as a valuable individual (even as most would not have cared one lick about the notion of providing education for all persons).

So is the problem science and technology? No – in fact, I think both Big data and MOOCs are likely able to be formed and used in good ways –with proper limits in mind. The question is “what is technology for”? My own answer, which I think is the right one, is that technology – like politics – should be for serving my neighbor. In politics, I should “vote for the other guy” and with technology, I should, through careful and thoughtful application (something akin to permaculture), look to serve my neighbor, and to do good for him and to him. But here is where we run into the crux of the problem: what we call the public good today is not understood to relate to the good, but rather what “works”. In other words, the “public good” today can best be understood as “the aggregate sum and fulfillment of as many individual’s desires as possible”, and this also is a result not of science and technology per se, but the MSTM.

What that has come to mean in today’s economy – looking more like a factory farm everyday – is that we need to be thinking first and foremost about efficiency and productivity – and if some individuals get run over by the locomotive known as the “technological imperative”, so be it. What can be done will be done indeed, as more traditional ways of feeling and thinking and living are blown apart and subsequently “re-purposed”. A cartoon lampooning Big data says it well: an airline official says to an arriving customer: “Your recent Amazon purchases, Tweet score and location history makes you 23.5% welcome here”.

Is this MSTM-driven notion of the “public good” – again, with its implications becoming clearer and clearer day by day – a sufficient concept by which to understand the world, much less to govern society? Perhaps Jaron Lanier has part of the answer when he, raging against the machine, asserts that “we are not gadgets”, and “we are better off believing we are special and not just machines”. We can call this “Lanier’s wager”, after the scientist and philosopher Blaise Pascal’s more famous one.

The problem with Lanier’s wager is that it simply amounts to his own private opinion – it is a “privatized humanism” and therefore does not compel. The same holds true for the views of Karl Marx, who believed that the dehumanizing aspects of capitalism led to the “fetishization” of the world of objects – which would then replace human beings as the objects of our affection. These views do not compel because with them, there is nothing “outside of us” that would command our admiration and devotion. Here is where we return to C.S. Lewis, that most creative of men, whose mind had been deeply formed by the classical liberal arts. In his brilliant and more or less non-religious book, The Abolition of Man, Lewis basically contended that the MSTM (not his language) had the power to “abolish” man. He made his argument that Western civilization was destroying itself by using a few simple sentences from an English textbook for middle school students.

In this textbook, Lewis points out that its authors, when talking about a waterfall, are careful to point out that we cannot say that the waterfall is “sublime” in itself – that is, intrinsically – but we can say that the waterfall provokes sublime feelings in the one who observes it. Lewis first of all points out that as regards feelings, the word “humble” is a more apt description and from that point on he is off to the races. He spends some thirty pages arguing convincingly that this simple move on the author’s part – where an objective goodness and beauty outside of the human being has been denied – has disastrous consequences for our lives together. In one of Lewis’ more memorable lines he states: “We make men without chests and expect from them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst.”

Lewis points out that men like Aristotle firmly believed that the aim of education was to make the pupil like and dislike what he ought, and that, in reality, this kind of “content-pushing” in education cannot be avoided. The main thing Lewis is getting at here is what Robin Lewis expresses in a bit different way: “Appreciating some artifacts are good in themselves, and not merely because of what they do for us, is the first step towards a proper appropriation of the liberal arts.”

To say this is true today, of course, is an uphill battle. As Nancy Maxwell wrote in her book about libraries, Sacred Stacks: “One of the only definite laws governing the postmodern academic world is that there are no definite laws. Belief in an overarching reality – one that purports to be the same for everyone regardless of perspective or personal stance – is no longer accepted at face value”. Applying this fact to library’s practical responsibilities on the ground, she says: “If there is nothing absolutely the same for all, how can one organizing principle apply? Attempting to organize all of human knowledge into ten categories – or even a thousand categories – seems a futile, even impossible task.” Maxwell goes on to talk about how “despite these limitations on their ability to organize knowledge, a perception still exists that libraries manage the task well enough”.

Of course no one is denying that libraries could not improve on this, one of their core services. And yet, note what is at issue: insofar as they are fighting the currents described above, librarians are fighting a losing battle on this and other fronts as well. After all, as she notes “if every person on earth has a legitimate way of viewing and organizing the world, there must be at least that many organizing systems…” On the contrary, it is good to seek a, or sometimes the, proper place for all the good objects that exist – the noticeable and interesting things that are worthy of attention and appreciation – even if not all recognize this. Here, the insight of Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, professor of Romance languages at Stanford University (the belly of the technological beast!) and author of “Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey” comes in handy: “there is probably no way to end the exclusive dominance of interpretation, to abandon hermeneutics… in the humanities without using concepts that potential intellectual opponents may polemically characterize as ‘substantialist,’ that is concepts such as ‘substance’ itself, ‘presence,’ and perhaps even ‘reality’ and ‘Being’.”

Geoffrey C. Bowker reminds us that “computers may have the data, but not everything in the world is given” (this is what the Latin datum means – something that “is a given”). This is true (hence Lewis spoke of education as “irrigating deserts”), and yet I think it is clear that Gumbrecht has a point as well – something like his approach is needed, and not only a “phenomenological approach”. Seemingly rigid taxonomies like those of Aristotle’s might unnerve us but what happens when the alternative means taking media guru Clay Shirkey’s phrase “metadata is worldview; sorting is a political act” – in a context increasingly skeptical about intrinsic goodness, beauty, justice and meaning – and mutating it into a mechanical act that “scales well”? (perhaps even under the guise that “the data are everything we need”, and “we do not even need to settle for models!”)

Those devoted to what have been librarianship’s core principles will increasingly need to search their souls, for as regards their venerable tradition it has already become “library science”. For example, “under the hood” technology that no one can understand is increasingly displacing instruction on the need to think hard about how real knowledge – and wisdom – might be organized and sought out by taking the time to learn the ins and outs of difficult research. As it stands, the current zeitgeist of the MSTM and its friend big business subsumes academic libraries and those who support them: technology is mysterious, even magical, and we, data-driven to the nth degree, simply need to quickly get our “customers” (do they want to be “customers”?) the information that will work for them and their purposes. Because we all “know” that what matters is that it “works for me” – until it no longer does, or course.

It was not only “arch-conservatives” like Lewis that had noted this relentless march of the MSTM. Noting the continual ascent of the scientific worldview in the late 18th century, the great German writer, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe believed that classical languages, classical literature, classical arts – and all meaning, ethics, and notions of cultural maturation (Bildung) – would be replaced by modern science and technology, where every tool would be used to maximize the power of human being – or some human beings that is. And what this means again is that any intrinsic or objective notion of goodness, love, majesty, beauty, honor, justice and meaning must leave the building. History is also a victim, for as prominent spokespersons of Big data assert: “The possession of knowledge which once meant an understanding of the past, is coming to mean an ability to predict the future”.

Small wonder there is such little trust among us. And as we give ourselves over to the lure of these things – seeking the power of technology apart from its rightful purposes – we in fact yield to the same pragmatism and reductionism those wielding them are captive to.

And perhaps we have not even begun to see the MSTM’s most bitter fruit. I submit that authors like Martin Ford, Jaron Lanier, and Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee are all being prophetic by making us more aware of how many are using technology to not only replace human muscle but the human mind, Big data being an integral part of this process. In spite of the sunny optimism that pours forth from Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s Second Machine Age, the writing seems very much to be on the wall: the encroachment will be relentless, as all must bow to the notion that what can be done must be done for progress’ sake – that is, the “technological imperative”, otherwise known as “Pandora’s Box”. This is why even persons associated with conservatism – men like N.Y. Times columnist David Brooks – can sum up the book by saying: “creativity can be described as the ability to grasp the essence of one thing, and then the essence of some very different thing, and smash them together to create some entirely new thing.”

Brooks may be being metaphorical here, but the wider point is that his notion of essence (he says “essentialists” will be rewarded in the new economy) would seem to have no relation to the classical views held by men like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and for that matter, those who wrote the Bible. Rather, the Brave New World is coming at us faster than ever before, where there is nothing that we currently call “good” that will not be up for grabs – at least in the minds of many. The science fiction writer William Gibson foresaw this in his 1984 novel Neuromancer, where, as in the 1927 silent picture Metropolis, certain characters experience liberation through technology but they are only able to do so because of the powerful corporate interests operating to the detriment of most persons. All of this is in fact, just like Lewis predicted in the Abolition of Man:

What we call Man’s power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument… For the power of Man to make himself what he pleases means… the power of some men to make other men what they please….[…mere nature to be kneaded and cut into new shapes for the pleasures of the masters who must, by hypothesis, have no motives but their own ‘natural’ impulses.] If man chooses himself as raw material to be manipulated, raw material he will be: not raw material to be manipulated as he fondly imagined, by himself, but by mere appetite, that is, mere Nature, in the person of his dehumanized Conditioners…..

Lewis’ comments here about MSTM in his day take on even greater relevance in the age of “information technology” and “Big data” – and one need not believe that most all of today’s elites are consciously trying to condition and enslave the masses to see the point Lewis is getting at.

It seems to me that, given the course we are all on, this looks to be our future. Contra Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, of course some men will be racing with the machines and not against them –the only questions are which men this will be, how they will race with the machines, and whether or not as a result of this process they will continue to act as men should.

Only some men will run with machines. Unless. Lewis was indeed a Christian, but again, his was by no means a Christian argument or an argument only Christians could understand. I suggest we all need to somehow get ourselves into the position where we can see the wisdom of what C.S. Lewis is saying. Somehow. We have been seduced by the MSTM, but what makes seduction evil is not its essence but its context. This surprisingly alluring “mechanical muse” of “information technology” and Big data need not serve as the microcosm of our Final Frontier. What we need – and can have – is a “good seduction” so to speak – one that is lasting and permanent, and one found by looking at our history. Come to think of it, not just librarians but each one of us – those in families, towns, cities, universities, and businesses – need that.

FIN

*That is almost always a plural you by the way – perhaps except when, for particular reasons, entities with particularly desirable quantities are desired. In any case, we are, generally speaking, talking about anonymized data here – this is, again, nothing personal. So this is in fact true whether it is a mass entity or a when particular entity – an “individual”, that is being singled out. Even the pinpointed individuals are not treated as persons to be known.